The Tempest

BIEFF - Bucharest International Experimental Film Festival, 2024

"Tell me you're not dangerous simply by being you and not me." Artist Alex Mirutziu engages in a poetic dialogue with the dominant narrator

— the master — of the popular online poppers trainer videos: that is, hyp-no-like found footage pornographic films made out of hundreds of short clips most often from hardcore porn combined with orders of submission ("listen to your master", "you're just a hole") and the instructions for inhaling poppers (soft vasodilators that relax the muscles). Much like a contemporary Jean Genet, Mirutziu talks to "the master" about love, sexual submission as beatification, the poetics of fluids and art as excretion of being, occupying the screen with his first-person indulged in thrilling visual violence of the image.

- Călin Boto, BIEFF 2024

Tracing Queer Narratives in Romanian Time-Based Media Art

Essay by Valentina Iancu

East European Film Bulletin, vol. 128, October 2022

Time-based media art that engages with queer politics is a very recent phenomenon in Romania. During Communism, the use of video technologies for artistic purposes was more or less illegal, while homosexuality was criminalized until 2001. The enormous effervescence of today’s visual art scene is the result of an accelerated and in many ways difficult process of reconnecting with and (re)discovering the rest of the world’s cultures that started immediately after the violent fall of Communism in 1989. On 25 December 1989, Nicolae Ceaușescu and his wife Elena were shot dead, after a military tribunal found them guilty of genocide. The video images of their execution traveled around the world, probably becoming the first televised spectacle of a dictator’s death. In the days that preceded the execution, around 1200 civilians were killed during nationwide protests in which Romanian citizens demanded the end of Communism. The traumatic events from December 1989 marked the end of an age of totalitarianism that had lasted for over half of the 20th century.

During the transition period much hope was placed in the promised freedoms of capitalism. It was a time of rapid socio-economical, cultural and political transformation. The return to private property, the rapid privatization of economic infrastructure, violent workers’ protests and a new wave of nationalism were plaguing Romanian society in the nineties. The art world was shifting to new perspectives, facing a need of major structural reconfigurations. The previous regime, together with its ideological limitations and censorship, had offered artists a system of privileges. But now, studios, galleries, acquisition programs for museums, fellowships etc. were suddenly gone. From one day to the other, the status of the artist, together with that of the Communist cultural institutions, vanished, slowly making way for the organization of a neoliberal art market. “New horizons appeared for the art worlds of former socialist states following the dismantling of the Iron Curtain and opening up of the borders between Central and Eastern European countries that had hindered the free flow of artistic exchange since the 1950s.”

Queer time-based media art is closely connected to the emergence of new art spaces and practices that started during the transition from Communism to neoliberal democracy. However, understood as a practice of body politics that resists oppressive sex/gender regimes, queer time-based media in Romania can be traced back to the works of earlier actionist artists such as Geta Brătescu and Ion Grigorescu. In that sense, the contemporary “revolution” of queer time-based media art in Romania displays a form of continuity that is in dialogue with the past. While new social constructions map new forms of social control onto the human body – in particular via the revitalization of the church and hetero-patriarchal capitalism – resisting dominant sex/gender regimes through deeply intimate and sensorial experiences thus remains essential to the artistic gesture of queering the body in Romania. In this essay, I wish to draw some parallels between contemporary and past Romanian time-based media art, in order to show how Romanian queer time-based media is shaped by different forms of political resistance ranging from personal emigration to Utopian escapism and from ironic performativity to political activism.

The rise of time-based media in Romania took place in the first decade of the nineties, at the very beginning of the post-Communist period. It was immediately marred by multiple scandals. Each new media exhibition organized at the beginning of the nineties was met with loud criticism. Romanian video art history needs to be written, re-written, re-thought and more deeply understood. During this period, video art as a medium can be considered queer in itself for the reactions it provoked in some circles of the art world. Ewin Kessler, the most vocal art critic of the time, wrote a series of articles that criticized the rise of video art in Romania:

In the Romanian artistic landscape, video art still remains a science fiction entry. For most, video art seems to be undesirable because it does not reflect the true level of socio-economic maturity of Romanian society, which has been dormant for so long in the antechamber of industrial civilizations […] permanently ravaged by those media storms in relation to which video art wants to be a barometer.

The opening of the Soros Center for Contemporary Art (CSAC) in 1993 accelerated the production of time-based media works and the discovery of experimental (private) artistic practices from past decades. It was the CSAC that financially supported the rise of new media art, organizing exhibitions, conferences, publishing books and creating an international art network. From its inception CSAS orchestrated three major projects: a financing line for socially engaged art (favoring time-based media and other experimental practices); an archive focused on contemporary art; and the organization of an annual exhibition dedicated to contemporary art. CSAS often commissioned socially engaged works for their annual time-based media exhibition. The initiative was received with hostile criticism. The strong debate around the guidance received by artists from the exhibition-making teams sparked accusations of “modeling” the “new artists”, pushing them in a direction of imitating the international creative trends in order to meet global standards. The changes of artistic practices were thus seen as forms of opportunism.

An important discovery of CSAC were clandestine video artworks that were made during the Communist years by a generation of experimental artists. Under the umbrella term “experimental art”, the art historian Alexadra Titu mustered all non-traditional visual artistic practices, such as video art, video installation, video performance, computer-based art, net art and so on. From Titu’s viewpoint, “the experiment as attitude, eluding or integrating the political, certainly is one of the integration strategies, but not only a strategy.”

The first video art exhibition “Ex Oriente Lux” opened its doors at Dalles exhibition hall in Bucharest in November 1993, inaugurating a series of annual exhibitions organized by CSAC. The show put on display ten commissioned video installations made by Alexandru Antik, Josef Bartha, Judith Egyed, Kisspal Szabolcs, Alexandru Patatics, Dan Perjovschi, Lia Perjovschi, subReal (Călin Dan & Josef Kiraly), Laszlo Ujvarpssy and Sorin Vreme. The exhibition was historically contextualized as neo-avantgarde and, with a few exceptions, negatively reviewed by the press. The second CSAC annual exhibition, “0101010”, gathered multimedia works by Horia Bernea, Gheorghe Ilea, Marilena Preda Sânc, Teodor Graur, Marcel Bunea, Radu Igazsag, Judit Egyed, Rudolf Kocsis, Ion Grigorescu, Alexandru Chira, Adrian Timar and intermedia Group at the National Museum of the Romanian Peasant.

CSAC commissioned socially engaged works, addressing current issues of Romanian society. The 010101 exhibition concentrated on reaffirming the role of artists as social catalyzers, the educational importance of art, as well as the political meaning of artistic practices. It was the beginning of “freak shows”, of poverty porn that focused on an exotic representation of various communities from the Roma minority. Poverty was a recurring subject and was addressed by the act of documenting the life of ethnically and racially marginalized communities. However, sexual or gender marginalization only played a minor role, if any. Despite the criticism they faced, some artists that had been given the opportunity to experiment with video art had taken the practice seriously and continued working with the medium. A case in point is Marilena Preda Sânc. CSAC exhibitions were non-normative in terms of being open to different subjects, methodologies of research as well artistic mediums.

In general, political topics were most often received with reservations, if not with hostility, by the contemporary Romanian art world. There was a fear of activism, a fear of political correctness, a fear of critical speech. With the memory of the programmatic politicization of art that dominated the Communist years still fresh, reservations to be branded as political and skepticism towards the politicization of art were widespread. On the other hand, neoliberal democracy brought about new problems such as racism, homophobia, nationalism, gender inequalities and poverty, not to mention the distribution of power inside the reshuffled art scene. Art historian Magda Cârneci remarks that by the end of the nineties, we can observe

moments when a political awareness of the urgency of change begins to develop in Romania, of the need to develop critical positions, but also the courage to assume irony, sarcasm, cruel humor and even nihilism against the local mental status quo. It is the moment when many artists begin to assert with enough determination unmistakable truths about inherited clichés and about historicalized, expired, obsolete cultural acquisitions.

The modest legacy of video works discovered in the context of CSAC, dating from the 70s and 80s, were the result of a process of documenting actions and performances taking place without an audience, in private places indoors or outdoors. Alienation, solitude, identity, surveillance, imprisonment, the human body, and nature were the subjects touched on by the actionist artworks of Geta Brătescu, Ion Grigorescu, Alexandru Antik and later by a younger generation spearheaded by Wandra Mihuleac, Aniko Gerendi, Decebal Scriba, Iulian Mereuță, and Lia Perjovschi, among others. The camera offered the illusion of artistic freedom: the artists had no official directives to follow and only limited information about the developments of the global video art scene. The access to technology was limited and highly regulated. Ion Grigorescu in Bucharest and the Sigma Artistic Group in Timișoara owned amateur Super 8 cameras and the kinema ikon group in Arad had access to a professional filmmaking apparatus. The conditions for producing clandestine experimental films were rudimentary. In their work, experimental artists explored their bodies, shifting towards subjectivity, psychology, and personal emotions. The body was a map of personal subjectivity, a form of internal emigration, which is why these works were later seen as a critique of Communist authority. Ileana Pintilie, who played a significant role in studying the body narratives in these films, singles out Ion Grigorescu (b. 1945) in particular, who she says was “undoubtedly the central figure of body-oriented artistic research in the 70s.”

Can a poetics of queer culture start here? Using an amateur Soviet camera, Ion Grigorescu’s performances in front of the camera were meant to explore his own flesh, the forbidden territory of nudity. He developed a complex photo-video archive of bodily expressions of feelings that he named a “scientific-mechanical” language. The video action Male and Female recorded in 1976 on 8mm film (black and white, silent) staged what can be understood as a “gender troubled” personality. The artist described his bodily experiences as multiple and complex, going outside the hegemonic understanding of the gender binary:

Penis as a paintbrush and masculine as a mask. On the one hand, it occupies a large part of my person, but no one should hold this place (for too long). She is a masculine conversation partner, although she uses a feminine name. She gives me an idea about myself and about my position in the world; she corrects a behavior that is inclined towards feminine. Our dialogue is not limited to the organic (things that we almost neglect); I have to acknowledge her intelligence, her ability to create, compose and imagine. As regards the status, your sensitivity is almost feminine, hysterical, morbid and febrile, with real language disorders. The more she asks about my personality, the more I tell her: I give you everything, that is, independence and authority, but not space, because there are others in the body too.

The video Male and Female softly touches on issues of gender transformation without having any awareness of gender theory. Grigorescu’s creative process is guided by intuitions in which vulnerability plays a crucial part. The ways in which this vulnerability is exposed in the creative process can be seen as a queering of masculinity. Grigorescu’s film shows how the complexities of the self cannot be fitted into gender norms. In that way, his film critiques the social pressure to perform the gender assigned at birth and the heteronormative regulations in a totalitarian society. Beyond gender politics, his experiments with the body might have a spiritual meaning as well, Grigorescu being interested in mythology, in particular myths of Androgyny, that fall outside the binary logic.

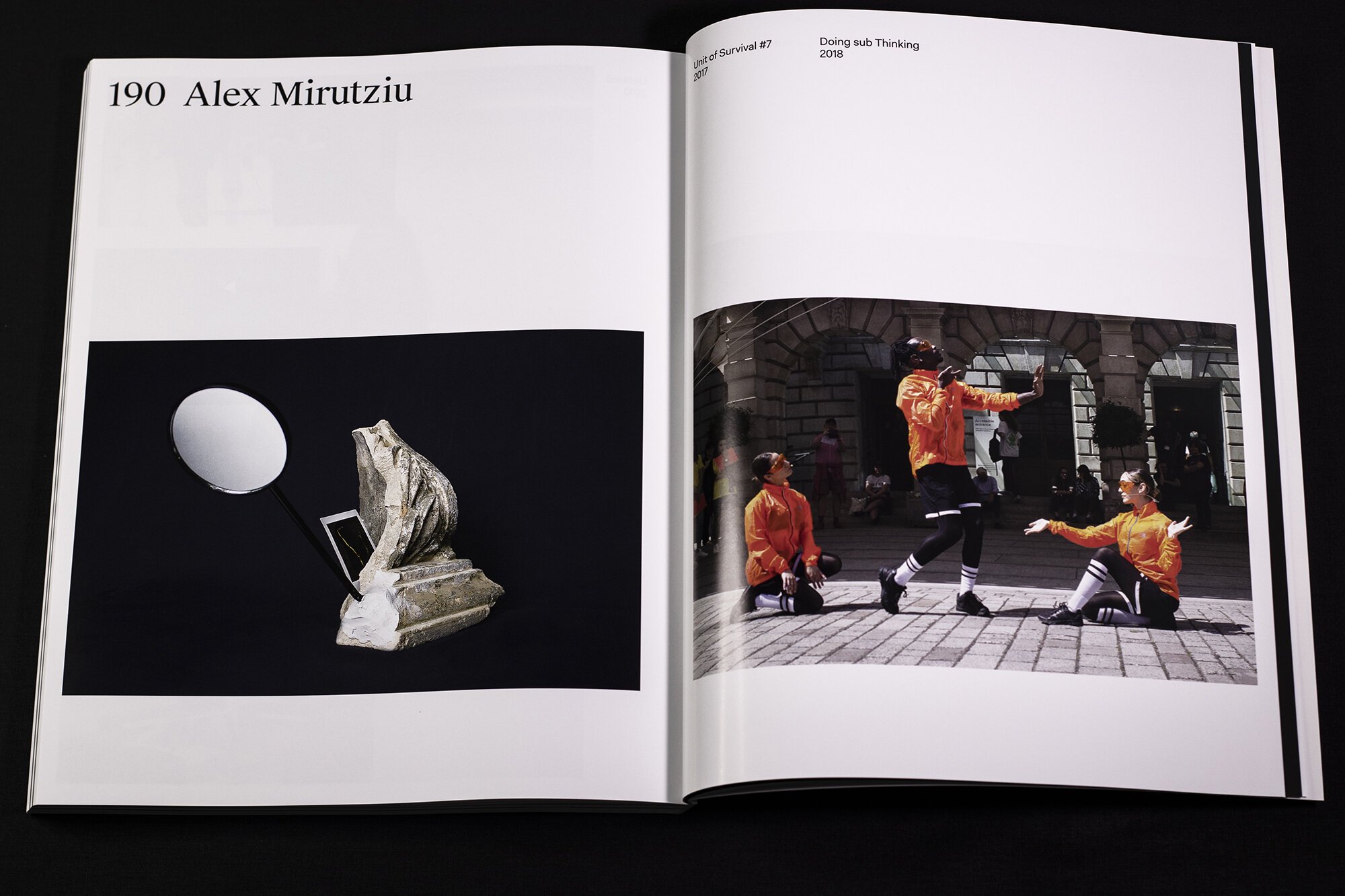

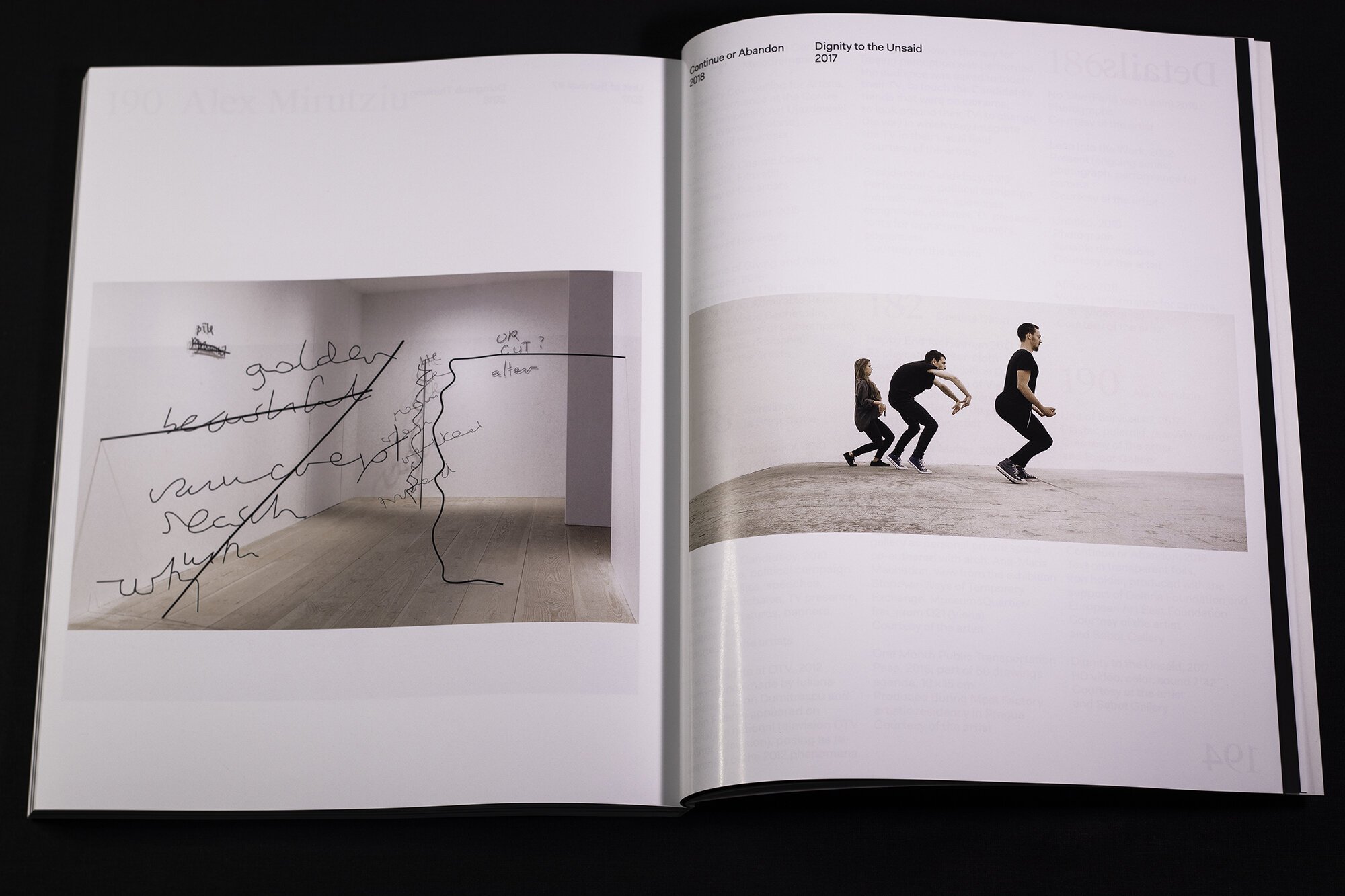

Ion Grigorescu’s unintentional queer touches were an inspiration for the young artist Alex Mirutziu (b. 1981), one of the first artists in Romania to consciously use a queer vocabulary. In his artworks, Mirutziu explicitly articulates his homosexual subjectivity, exploring his own desire, love, fear, pulsation and compulsion. Mirutziu centers his work on the body, often using his body to return the gaze, while making subtle sense of a “sinful and pathological” desire. Alex Mirutziu finished his visual art studies in Cluj-Napoca in 2001, the same year that homosexuality was decriminalized. He is a multidisciplinary artist working with performance, video art, theoretical texts, poetry, and drawing. His politics are oriented toward personal poetics, queerness being implicit, often abstract. Mirutziu makes use of metaphor to form an abstract queer vocabulary, understanding his art as “a protest”. Mirutziu only began including video art in his practice in 2017, extending some performances in new video art works. He doesn’t consider the documentation of a performance a work of art. Similarly, a video-documentation of a painting may not be seen as a new piece of art. His video performances Dignity to the Unsaid, The Gaze is a Prolapse Dressed in Big Business (2018) and Bottoms Know It (2019) have performances as a starting point but end up as unique video artworks often incorporating new scenarios. Mirutziu builds his subjects rhizomatically, carefully connecting ideas so as not to fall into categorical thinking. His work investigates queer issues, mixing theoretical approaches with intuition. For example, Bottoms Know It aims to give access to a distinct type of knowledge, that of the complicated relationship we have with our assholes. Centered on the poetics of anality, hence of openings, entrances, closings, exits, centers, and holes it deploys means of seeing and understanding the world and the ‘other’ taking disappearance and debasing of the self as the subject and gateway to a more profound grasp of our humanity.

In the performance/video, three local performers (dancers) are put into situations of visual alienation. Conversing and debating about the limitations of the body, they engage in an absurdist philosophical dialogue. Anal poetics is a way of queering a penis-oriented masculinity. Anal pleasure is seen as a pathological pleasure and as a feminizing pleasure. It is hence often refused by heterosexual males out of fear of homosexuality, largely being associated with gay sexuality.

Alex Mirutziu’s complex explorations of the homosexual body and his inventory of gestures undoing masculinity often touch on religious taboos. The use of Christian symbols in his art can be seen as a powerful way of queering himself, of liberating his symbolic body from the prison of sin. The idea of sin is very present in Romanian homophobic narratives, as the strongest opposition to homosexuality comes from the Orthodox Church, a highly influential institution both inside the state apparatus and within societal structures. Hand in hand with the church, conservative political groups were protesting against homosexual liberation, perceived as something foreign that was closely associated with Western Europe: “Romania wants to join Europe, not Sodom”. In Romanian national myths, the collective symbolic body is identified with the homophobic claims of Christian Orthodoxy.

Part of the construction and preservation of any myth is the exclusion of whatever falls out of the intended narrative. From the simple perspective of statehood, individual bodies reproduce themselves inside nuclear families while working inside capitalist survival economies. The aesthetics of such national bodies associate ability and obedience with religious values. In the process of instituting dominant regimes centered on material production and heteronormative reproduction, some bodies, in this case queer bodies, fall out of the collective national body. Since the national body is in part defined by what it excludes, the narratives it creates to uphold its gender norms can be seen as a form of symbolic violence against those diverting from such norms. Art plays a key part in this process.

An aesthetic concerned with narrating the queer body should thus pay attention to excluded bodies, bodies often targeted by violence. A body that performs an aesthetic different from “the national body”, be it in its life choices, its fashion or even its inventory of gestures and body movements, is a fascinating subject (an object of desire) for artists and at the same time a target for violence (transphobia, lesbophobia or racism).

Alex Mirutziu’s narratives challenge the national body in a way that complements Katja Lee Eliad’s abstractions of lesbian subjectivity. Katja Lee Eliad, a multidisciplinary artist who works with drawing, poetry, painting, and time-based media art often records actions done in the studio or outside, the camera becoming a spectator, witness, and self-surveillance tool. For example, Perform is a poetical reflection on mental health and the abstract language of psychiatric diagnosis. How does a diagnosis affect our mind and behavior? Through the means of a video-performance, she staged an investigation of pain and its effects on the body. The performance compiles footage of skateboard exercises (specifically falls) where Katja stages skateboarding accidents in order to contemplate the crash, the falling, and their effects on the body. The attempt to signify the fall comes from a desire for understanding pain beyond the psychologically pathological. Most information we have about the experience of a mental breakdown comes from external psychiatric observation, rarely from self-study. Through the means of a cathartic artistic process, Katja stages a Cartesian doubt on what we know about brain circuits, affects, the human mind, the body, and the relationships between them. The strong connection between psychoanalysis and spirituality is often a subject of philosophical reflection as the fall and repetition resemble ritualistic processes. Eliad, exactly as Ion Grigorescu, is a spiritual person, and her imagination is rooted in mysticism and mythology, but she intentionally plays with overlapping significations. Spirituality, especially ideas originating in non-white religions, can expand our understanding on yet fragile topics such as gender or same-sex desire, offering alternative views to the dominant Christian Orthodox religion.

European homophobia and transphobia are strongly rooted in religion, therefore a more inclusive spiritual narrative can add some positive tension to the very strong notion of “sin” attached to the queer symbolic body. What are the mythologies of “sin” that justify and normalize the violence against the queer body? A political video that goes deep into questioning the relationship between “sin” and the queer body is Bahlui Arcadia, signed by the artistic duo Simona and Ramona. Simona Dumitriu and Ramona Dima are life partners, working together as an artistic duo since 2014. Since then, they have explored issues connected to gender, sexuality, and non-normative life in general. Inspired by Renate Lorenz’s methodology for making “freaky” queer art, Bahlui Arcadia consists of two superimposed components: a video screening at the artists’ home and a long performance taking place at the same time on the shores of the Nicolina river at its confluence with the river Bahlui, where Simona grew up as a young child. Simona and Ramona are blurring the lines between art, existentialism and politics. Their artistic practice starts from finding meaning in personal subjectivity, which is always understood in a feminist sense as political: “I try to live and to work starting from a set of ethical rules: to not instrumentalize the experience of other persons, to take my own privileges into account, and to speak about what I know, using a language that is as undiscriminating and without able-ing as possible.”

The video Bahlui Arcadia shows Simona exercising on a stepper outside, in a green space behind some Communist housing blocks. The scene takes place in Simona’s childhood Arcadia, a small green area near the Bahlui River. In the background we can hear a conversation between Simona and Ramona, an intimate dialogue filled with memories, fantasies, and reflections about religion, desire, and ordinary life experiences. The non-linear dialogue is a reflection on the notion of “sin”: the recently renovated blocks of flats from the area where Simona grew up were filled with religious quotations (e.g., quotes from the Bible written on walls). Embodying condemned bodies engaged in an act of sinful love, Simona and Ramona’s work can be seen as a moving poetic visualization of the lesbian body, a powerful story that sews together multiple narratives that shed light on what it means to become a lesbian and navigate the meanings of being Eastern European, Romanian, precarious, Christian, white, female, and educated without falling under any of these possible identarian and constructed categorizations. An old-fashioned love letter softly introduces the viewer’s gaze to the intimacy of lesbian seduction. At one point in the video, Simona introduces Claude, her drag persona:

What is Claude? A wannabe Catholic priest, the poetic centennial result of the generic liberations brought by the avant-garde somewhere else, a moral being, a leaflet of queer feminist ethics propaganda found 50 years later in a vintage edition of Better Homes and Gardens magazine. Claude was Cahun asking in Aveux non Avenus ‘Surely you are not claiming to be more homosexual than I… ?’ when meeting her postmodern multiples in the ’90s. Confronted to the absence of non-normative stories in history, Claude asks himself ‘Can I become a municipal legend, ready to wear my drag persona as repair of this absence and resistance against the local reproductive machine?

Ramona begins creating Dersch: “What is Dersch? A found object. Contemporary militaria, a piece of cloth randomly retrieved from bric-à-brac. USA official Marine army jacket, size M with NATO identification label.” The work touches on various mythologies strongly connected to the local experience of this specific geography, asking questions about how the lesbian symbolic body is affected by national myths, and especially Christian Orthodoxy.

Alex Mirutziu, Simona Dumitriu & Ramona Dima, Katja Lee Eliad, Sorin Oncu (1980-2016), Manuel Pelmuș, Veda Popovici, Alexandra Ivanciu & Anastasia Jurăscu or Hortensia Mi Kafkin (Kafchin) were pioneers in the field of queer time-based media art. None of them can be considered a “video artist”. They all pursue a multidisciplinary approach, which sometimes includes video. Today, the queer scene is growing very fast. With the internet especially, more and more time-based works touching on queer issues are put on display in various exhibitions. The rise of queer culture started as an alliance between various artistic initiatives and LGBTQ+-right activists. The collaboration between activists, artists, and curators often resorts to a methodology that calls to mind the annual exhibitions organized by CSAC. Commissioned art and solidarity-exhibitions are often financed by NGOs: this led to a new precarious periphery that is still in the process of being recognized.

One of the most active artists in the activist movement was Sorin Oncu, whose artistic practice closely follows an activist agenda. Oncu thus often explored and exposed the topic of his own homosexual masculinity, engaging his art in the fight for homosexual rights. Although his homosexuality was the main topic of his artistic research, he never put images of his own body on display. One exception is his first artivist (art+activism) installation, which he made in the context of a local LGBT-rights NGO, LGBTeam in Timișoara. The work Coming Out included some photographs of him and his partner in intimate gestures. After that his focus shifted towards more general activist claims in accordance with his experiences of discrimination as a homosexual male and a non-European citizen (Oncu was born in Serbia). During 2004-2007 he worked on several series inspired by the dynamics of LGBTQ+ life and the problems faced by homosexuals in post-Communist Romania, most of them being presented in group shows in Timişoara. During those years, he joined the LGBTeam association, getting involved in various activist and educational actions that aim at acknowledging diversity. During this time, the artist worked with flat surfaces, using painting, sketching and collage as his main techniques. Over time, his interest steered towards the bidimensional, opting for the arte povera language in installations of found objects that acquired new meanings via recontextualization. He explored multiple experimental territories: video, animation, found or built assemblages (out of very unusual materials). He considered himself a protest-artist with a critical vocation who “exercises this vocation freely associated with the minorities’ side in a democratic and pluralist society.” Due to his strong political activism, he existed at the fringes of the visual art scene. The connection between activism and visual arts started to grow in Romania after his premature death in 2016. In 2018 a referendum for changing the definition of the family in the Romanian constitution was held. Backed by a highly homophobic campaign, the measure would have made same-sex marriage unconstitutional. The referendum failed, however, as the voter turnout was below the threshold. The homophobic pressure surrounding the referendum succeeded to connect culture and activism, accelerating the steps of what has recently been seen as a “queer revolution.”

Queer politics usually departs from the body, real or symbolic, collective or individual. It does so in opposition to sex/gender regimes that normalize, chastise, or criminalize this body. From this point of view, Ion Grigorescu’s reflections on the body that include, for example, one photography staging a ritualistic castration, can be understood through the lens of queer politics or queering. Is Ion Grigorescu a precursor of queer time-based media art? Is it fair to attach new theories to old works and reflect on meanings that were not necessarily of concern for the artist? Grigorescu’s way of narrating the body resonates with the queer symbolic body narratives built by the first generations of queer artists making time-based media art in Romania. In that way, it may be more adequate to speak about an evolution instead of a revolution. For example, the topic of castration is a subject represented by Hortensia Mi Kafkin (Kafchin), an artist concerned with transgender issues. Kafkin is interested in spirituality as well, with her witch alter ego cutting her own penis (shenis) in a ritual.

The coming out as a transgender woman of Hortensia Mi Kafkin, through the exhibition “Self-Fulfilling Prophecy” (Judin Galerie, 2016), directly pointed to transgender issues in the Romanian visual art scene. Hortensia Mi Kafkin is a multidisciplinary artist, a visionary dreamer who was already recognized and acclaimed by the local art scene at the moment of her coming out. Transition, transgender subjectivity, and transformation are central themes in her work. Here, bodies change into machines, which appeared in her work long before her coming out, as did witches, reptiles, enhanced humans, and aliens. Hortensia Mi Kafkin’s art conceives a universe filled with the magic of fantasies. She often says that she “is her art”, understanding that her creative endeavors keep her alive. She adapts to the hostile gender norms by dreaming and taking long journeys into the realm of imagination, which she records in various mediums such as drawing, painting, sculpture, 3D sculptures or other digital new technologies, installations, or video art.

In her most well-known video art works Personal Hawking and Bald Commercial, both produced with the support of Sabot gallery from Cluj-Napoca, she develops an aesthetic of the monstrous. The monstrous can convey feelings of surviving the hostile sex/gender regime, staying outside, dreaming in isolation. In Personal Hawking we see the artist performing a seductive demon teaching science, while in Bald Commercial she uses a replica of Brâncuși’s iconic Madame Pogany bronze and a wig, with the bronze figure turning bald over the course of the video. The work uses a punk-pop aesthetic and extraterrestrial iconography (the sculpture has alien eyes). The personal feeling of discomfort and of owning a monstrous body is a recurring topic in Hortensia’s work. Hortensia’s art can be seen as a surreal diary of multiple transitions, which can be interpreted as a queer gesture after her coming out. She had never claimed a queer space before starting the transition, leaving her metaphors unexplained. Her visual language throughout her body of work is implicitly political, articulating a personal queer poetics, but without engaging an activist agenda. She is more recognized in the art world and operates outside the activist scene.

Reality is changing fast. The rise of digital and post-internet art is lately opening up a new chapter on queer time-based media art in culture, extending the explorations to hybrid bodies, non-human emotions, sex ecologies, bacterial subjectivity, and alien experiences with young new voices.

Virusarea identității în era corpului docil/ carantinat/ fără organe

Text de Raluca Oancea (Nestor)

Revista Arta, Martie 11, 2021

RO:

Într-o perioadă traumatică a insecurității și a afectelor mediatice dezlănțuite, în care pandemia COVID 19 provoacă disoluția treptată a comunicării naturale, scena artistică se zbate să rămână în viață, să se implice în procesul atât de necesar de mediere, de dezbatere a unor teme actuale și totodată dureroase. În acest context problematic, expoziția Identitate Ultragiată s-a dovedit oportună, atât ca prilej de resuscitare a unei scene artistice anesteziate de pandemie cât și ca bun prilej de reflecție asupra modului în care astăzi ne privim, ne (re)cunoaștem și ne (re)construim pe noi înșine.

Inițiat de experimentata curatoare Ileana Pintilie, relevantul demers de chestionare a identității în epoca prefixelor post (postmodernitate, postfeminism, postumanism) a adunat media și abordări variate din centre culturale ca București, Cluj, Timișoara, sub egida unei critici ce vizează atât limitările unei societăți bazate pe uniformizare și consum, cât și discriminarea (ultragiere, rănire, virusare, atac) pe motive de gen, orientare sexuală sau locație periferică. Problemelor anticipate de curator și artiști precum cea a propriei lipse de libertate și putere ca actanți ai unei scene dominate de centre de forță instituționale și scheme financiare, cea a intruziunii tehnologice în sfera identității și a autenticității (sinelui, artei), pandemia le-a adăugat un nou layer marcat de înlocuirea atingerii și a comunicării fizice cu interacțiunea la distanță, includerea măștii în pattern-ul feței umane.

În consecință, sondarea identității a fost pusă în relație atât cu tema corpului (fie acesta docil după modelul lui Faucault, fără organe după Deleuze, ori bolnav/carantinat/ închis ermetic într-un sac cu fermoar conform ecuației pandemice actuale) cât și cu cea a tipurilor de media implicate în procesul de analiză și deconspirare artistică a unei identități. Din poziția sa de reputat critic și istoric de artă, Ileana Pintilie a lansat întrebări relevante precum: ce mai presupun astăzi noțiunile de portret, autoportret, acțiune, cum reușește imaginea tehnică să capteze aura și expresivitatea necesară unor astfel de demersuri, cum evoluează relația dintre identitate și autenticitate în era reproducerii mecanice/tehnologice. Investigația a chestionat și modul în care într-o epocă a post performance-ului, în care de multe ori artistul renunță la prezența sa efectivă, retrăgându-se într-o reprezentare, arta mai poate funcționa cathartic pentru genuri, subculturi, comunități defavorizate.

Printre cele cinci abordări intermediale incluse în demersul expozițional, cea a Pushei Petrov abordează cel mai explicit problematica subculturilor. În opinia mea lucrările incluse în expoziția de la București continuă și aprofundează cercetările sale artistice plasate sub semnul erotismului, culturii populare și al asumării sensibilității camp (vezi seria de genți roz, ușor desfăcute, privite de sus, ce amintesc imaginea unei flori deschise sau a organului sexual femeiesc, Marsupium à main, Art Encounters, 2017), adăugând layere antropologice, etnologice, ontologice (finitudine, timp).

Lucrările prezentate la București fac parte, de altfel, dintr-o cercetare artistică mai amplă întreprinsă la Paris în saloanele de coafură africană din zona Gării de Est, în scopul de a explora modul în care părul poate constitui un medium de expresie artistică. Seria de portrete fotografice de mari dimensiuni ale unor împletiturilor capilare africane, (des)coase, 2019, revelează părul ca limbaj, medium artistic, amprentă, tabu. Sunt scoase astfel din ascundere conotațiile erotice ale părului feminin în culturile orientale, statutul acestuia de lucru aproape viu, aproape sacru, ce trebuie ascuns, prins, legat, capacitatea acestuia de a fascina și a înspăimânta totodată, de a încapsula un raport de putere asemeni obiectului de cult.

Pentru Pusha Petrov, aparținând ea însăși unei comunități etnice restrânse de bulgari din Banat, centrul de greutate al proiectului rezidă însă în latura sa participativă. în vizitele la saloanele din Paris unde de regulă se atașează extensii și în conversațiile purtate aici cu membrii comunității. După ce părul artistei a fost împletit și transformat într-o arhitectură organică de către artistele africane, Pusha Petrov a inițiat un nou performance colaborativ, în care mai mulți artiști au intervenit alături de ea asupra arhitecturii capilare cu fire colorate. Observăm aici cum gestul de a coase în păr, cu alt fir decât cel negru folosit de regulă pentru a ascunde actul construirii, cât și cel de a coase împreună, fiecare după legi proprii dar în contextul aceleiași platforme de comunicare, pot fi interpretate ca subtile comentarii aduse de-construcției ca metodă artistică cât și modului în care identitatea noastră se construiește în oglindă (vezi Lacan) și în lume (în raport cu o anumită comunitate, valori, istorie).

Acestui proiect intermedial, situat la intersecția fotografiei cu performanceul și practica body art, i se alătură instalația sonoră Chignon Chouchou (2019), o serie de cocuri împletite în același stil, ce relatează (cu ajutorul unor boxe inserate) mituri urbane construite în jurul podoabelor capilare. Proiectele constituie atât un comentariu pertinent la adresa disoluției genurilor și a limbajelor artistice specifice cât și un discurs existențial, conturat în jurul dezbătutelor dihotomii dintre a fi și a părea (aici extensia de păr oscilează între statutul simplei aparențe și cel al unei linii de fugă către teritoriul vast al trans-umanului), dintre cele două interpretări ale femeii: femeia ca obiect natural și frumoasă aparență (frumusețe vegetală, lipsită de spirit) respectiv femeia ca operă de artă, ca esență și spirit liber a-și remodela aparența.

Pe linia trasată de estetica pragmatistă a lui John Dewey (Arta ca experiență), reluată recent de Richard Shusterman, cercetarea Pushei Petrov din saloanele africane confirmă faptul că aranjarea părului constituie totodată un episod autentic al vieții cotidiene cât și o experiență estetică capabilă a strânge laolaltă o comunitate (fie și pentru o după amiază într-o încăpere modestă, cu scaune și perdele uzate). În acest context practica artistică se încarcă cu valoare existențială, devine un prilej de a dezbate și promova un set de valori și credințe (alternative) capabile a contura fundalul unei existențe și trasarea unei identități în funcție de apartenența la subcultura respectivă.

O a treia lucrare, l’image qu’on a jamais, funcționează după principiul surprizei, al unghiului neașteptat sau al deformării practicate în pictura manieristă sau în filmul expresionist. Ceea ce inițial aduce cu o serie de portrete fără trăsături sau hărți misterioase se dovedește a fi reprezentarea unor creștete despădurite văzute de sus, o serie de configurații alopeciale. Caracterul universal al acestor chipuri fără chip, capabile a revela finitudinea umană marcată de fiecare clipă ce devine la rândul său trecut, de durata bergsoniană, este potențată de tehnica prețioasă a digigrafiei și de ramele aurii.

Un prețios comentariu asupra finitudinii oferă la rândul său artista Olivia Mihălțianu în proiectul Self Portrait as a Drowned Artist and The Portrait Studio (2020). Titlul deconspiră o reinterpretare a celebrului La noyade (1840), autoportretul manifest al lui Hippolyte Bayard, marele pierzător al patentului de inventator al fotografiei în fața celebrului Daguerre, om de știință susținut de Academia Franceză. Într-o inedită încercare de a așeza într-o unică ecuație problema identității și a finitudinii, condiția artistului și modul în care tehnologia influențează practica artistică, Olivia Mihălțianu reia mesajul lui Bayard care, grație paradoxalului său autoportret ca înecat, reușește să sfideze capriciile sorții și limitările tehnologiei (un portret necesita atunci imobilizarea subiectului și închiderea ochilor), încăpățânându-se să rămână în istoria artei fie și ca întemeietor al fotografiei înscenate.

Combinând o incitantă sinteză media (fotografie, video, sculptură) cu teme predilecte precum autoportretul și jocul de roluri (începând cu expoziția Femidon, Galeria Nouă, 2007), raportul fragil dintre natură și tehnologie (vezi intervențiile în natură din grădina Tranzit sau contribuțiile la expozițiile DPlatform, 2018), Olivia Mihălțianu livrează un comentariu matur ce conectează portretul cu tehnologia, poziționează practica foto-video pe linia fină dintre estetic și tehnologic. Cu alte cuvinte, imaginea produsă cu ajutorul unui aparat, desconsiderată adesea ca simplu mijloc de mimesis, de înregistrare a realității își revelează aici abilitățile de unealtă magică, spirituală (Robert Bresson) ce poate capta frumosul, aura, identitatea. Frumusețea tehnicii, a aparatului și a metodologiei sale de lucru, bazată pe substanțe chimice, erori, reușite, se alătură frumuseții naturale.

Instalația Self Portrait as a Drowned Artist and The Portrait Studio, în opinia mea cea mai puternică prezență a demersului expozițional discutat, se distinge prin conturarea unui spațiu în spațiu, prin delimitarea unei felii independente de spațiu-timp. Cu alte cuvinte, artista construiește într-una dintre sălile galeriei o replică a atelierului său din Sofia, în care alături de sculptorul Stoyan Dechev s-a dedicat studiului și înregistrării intermediale a corpului și identității umane, în funcție de perspectivă și lumină. Subtila înțelegere a spațiului o redefinește pe absolventa de Foto-Video drept artist transmedial ilustrând în același timp diferența dintre simplul fotograf (în cuvintele lui Vilem Flusser funcționarul aparatului său) și artistul care lucrează cu fotografia (filmul) sondând limitele imaginii tehnice și interferența sa cu practica tradițională (portret, peisaj).

Spațiul este organizat în patru celule dintre care primele două par a fi dedicate imaginii frumoase ce favorizează contemplarea readucând în discuție studiile anterioare ale artistei asupra naturii dar și sensibilele ei cianotipii realizate uneori în contexte performativ-participative (vechea tehnică a cianotipiei a fost practicată de Bayard însuși). În prima celulă, pentru a evoca statutul fragil al artistului contemporan dar și relația fotografiei cu limitarea corpului, Olivia Mihălțianu alătură un sensibil și prețios print pe bază de sare, ce reia postura înecatului cufundat într-un somn vindecător, unei serii de tije metalice ce invocă suporturile folosite la începutul fotografiei pentru imobilizarea subiectului. Frumoasa fotografie portocalie antrenează conotații multiple, de la imaginea Ofeliei plutind pe apă, calmă, imobilă și seninătatea sepia a fotografiilor mortuare, la redefinirea contemplării (ca soluție asumată a refugierii temporare în vis, în frumusețea liniștitoare) și deconspirarea principiului vechii fotografii în care prețul imortalității reprezentării era plătit printr-un lung exercițiu de imobilizare a corpului în fața camerei. A doua celulă este dominată de un video în care imagini din atelierul din Sofia al artistei întâlnesc imagini din grădina campusului ce îl găzduiește, inclusiv cea a unui bust abandonat de femeie pe care ploaia și vegetația și-au lăsat urmele.

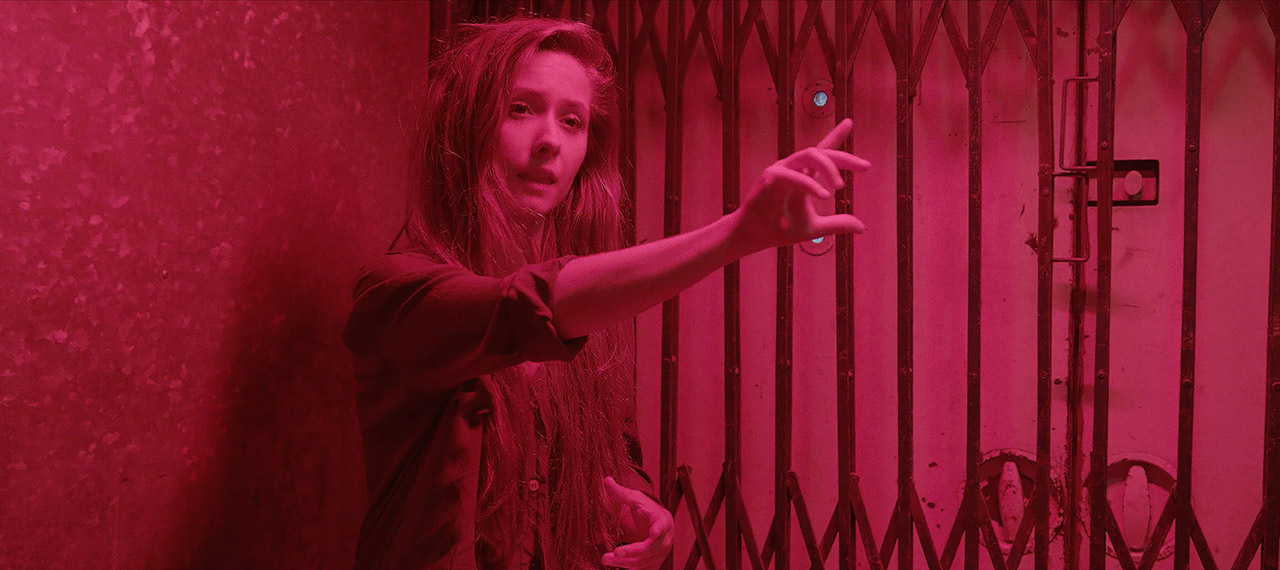

Dacă primele surprindeau prin frumusețea apolinică și îndemnau la contemplare, ultimele celule se definesc ca teritoriu dionisiac al acțiunii: ruperea visului, recontextualizarea protestului lui Bayard pe o scenă artistică dominată de instituții și valoare de piață. Astfel, o a treia cameră, goală, inundată de o lumină roșie ce conferă spațiului o coordonată afectivă, îmbină trăsăturile unui laborator foto, în care developarea poate impune o temporară suspendare a simțului dominant al vederii, cu tensiunea actului erotic, transgresiv, cu aducerea (oricât de dureroasă) la viață. La rândul său, ultima cameră reprezintă un studio foto re-contextualizat în epoca selfie în care tot mai mulți oameni aleg să își realizeze singuri portretul. Aici publicul este invitat să folosească recuzita necesară (un suport pentru cap, setup de lumini pe care mulți și le-au amenajat deja acasă în vederea interacțiunii online din pandemie) realizând un selfie cu propriul telefon.

Imersiv și interactiv proiectul lansează astfel un captivant comentariu asupra evoluției imaginii tehnice, de la primele încercări de a fixa o reprezentare într-o fotografie și până la produsele tipice erei digitale, celebrele selfie, înscenate și prefabricate, create pentru a fi manipulate și distribuite în masă. Simultan, practica artistică este definită ca act dureros și transgresiv, plasat la întâlnirea inspirației și imaginației nelimitate cu finitudinea și condiția tragică a umanității.

Cu un pas mai departe pe linia transgresiunii se situează Adriana Jebeleanu, artistă care în 2012 a ales dispariția de pe scena artei dar și a vieții. Povestea acestei identități rănite și anulate este prezentată odată cu explorarea registrului tragicului, al straniului, al informului, al sublimului într-o serie de lucrări cu tentă afectivă, bazate pe contrastul dintre nonculori (alb, negru) și roșul puternic. Caracterul transmedial al acestor acțiuni ce sunt pe rând fotografiate, filmate sau desfășurate în fața publicului se îmbină cu orientarea anti-artă, revelând o acută criză a reprezentării simțită de artista formată ca pictoriță. Un exemplu în acest sens Blind, Deaf, Mute (2011), în care artista cu capul acoperit de o cagulă (albă, roșie, neagră) stă în fața unui pian fără a-i atinge clapele, reinterpretează celebrul 4 minute și 33 de secunde al lui John Cage.

Imposibilitatea comunicării o face pe artistă să penduleze între soluția romantică a retragerii din lume, a proiecției de realități onirice, deconectate, respectiv implicarea în acțiuni cathartice ce constituie atât un mod de protest cât și o încercare de ieșire din sine, către celălalt. În acest scop starea de vis, urma, absența vor alterna cu prezența, cu cât mai tăcută, mai abstractă, cu atât mai apăsătoare.

Registrul retragerii este ilustrat atât de performance-ul cu capul acoperit Orb, surd, mut cât și de videouri scurte ca I will forget, 2009, construit în jurul dihotomiilor aparență-prezență, veșmânt-corp, corp-spirit. Dacă în primul caz soluția pare a fi sondarea interiorității profunde (angoase, dorințe, pulsiuni) în căutarea ultimelor urme ale autenticității, în cel de-al doilea o serie de veșminte albe, agățate în pădure deconspiră lipsa corpului, artista întoarcându-se către natura încă liberă, către modelul creației spontane. Registrul acțiunii este implicat atunci când artista se hotărăște să privească spectatorul în ochi, direct în contextul unui performance sau mediat prin intermediul unui video ca FAST FOOD, 2008, un protest împotriva lipsei autenticității și a ritmului mașinizant al vieții, în care artista îmbrăcată în alb mănâncă petalele unui crin. Chiar și în varianta video, privirea sa pătrunzătoare depășește nivelul optic înscriindu-se în zona hapticului, a privirii care atinge (the gaze), care neliniștește publicul îndemnându-l la acțiune.

Videouri ca Totally Love (2011) în care un lichid sângeriu se revarsă continuu peste marginile unei căni invocă legătura dintre autenticitate și angoasă, actul ieșirii din sine, actul vărsării din corp, al topirii contururilor dureroase care ne separă iremediabil de celălalt, act ce devine posibil (după cum ne avertizează George Bataille) numai în erotism sau în moarte. Depășirea lumii conformismului, a vidului identitar, a mașinizării trăirii, a șablonizării artei determină astfel angrenarea artistei într-un proces transgresiv de sondare a limitelor psihologice, a frontierelor conștiinței readucând în discuție definiția artistului modern dată de Susan Sontag ca broker al nebuniei. În acest sens, trebuie să acceptăm că practica artistică cu miză cathartică, actul performativ dus până la capăt, până la depășirea limitelor fizice, corporale, recuperează perimetrul sacrului dar în același timp se dovedește riscantă pentru artist ca persoană. În cazul Adrianei Jebeleanu, prețul plătit pentru autenticitatea ultimă, pentru experimentarea ieșirii din sine, pentru trăirea acută a limitei, care în opinia lui Bataille solicită “aprobarea vieții până și în moarte”, va fi trecerea dincolo.

Un demers înrudit, înscris pe aceeași traiectorie a finitudinii și transgresivității este cel al artistului clujean Alex Miruțiu care în cele două lucrări expuse la București testează limitele corpului și ale identității de gen și orientare sexuală. În Feeding the Horses of all heroes, 2010, performance înregistrat la Accademia di Romania din Roma, instituție conservatoare, artistul se lansează într-un exercițiu cathartic al căderii și recuperării. Travestit într-un model de modă, obiect predefinit al admirației, și înarmat cu recuzita corespunzătoare (pantofi cu toc înalt, ținute senzuale, expresie absentă, de nepătruns), el parcurge recurent un catwalk sub privirea atentă a publicului. Chiar dacă pentru o scurtă perioadă el pare a se conforma identității de vedetă specializată în trăire aparentă, artistul rupe parcurgerea ritmică printr-o neașteptată cădere (gest marcat sonor cu un dramatic zgomot metalic, dizarmonic) care apoi se va repeta ritmic. Acest ritual al căderii (coordonată existențială asociată de filosofi cu pierderea sinelui autentic în favoarea unor trăsături impersonale: ce se spune, se crede, se poartă) pare a invoca nu doar condiția artistului și instituția fashion-ului ci întreaga societate a spectacolului (Guy Debord) în care astăzi ne trezim angrenați ca dispozitive, corpuri docile, organe, spectatori anesteziați și izolați, identități prefabricate.

Contrastul dintre cădere și recuperare readuce în discuție cercetările lui Mirutziu asupra luptei scriitoarei Iris Murdoch cu pierderea memoriei și maladia Alzheimer, confirmând abilitatea artistului de a scoate din ascundere finitudinea umană, limitele corpului, voinței, limbajului, anduranței, de a recupera frumusețea și eroismul ce inevitabil se ascund în eroare, în fragilitatea umană. Același contrast revelează un nou tip de tensiune, tensiunea ființei umane între verticalitate și orizontalitate. În acest sens Mirutziu aderă după modelul lui Bataille și Rosalind Kraus la o estetică a informului, a materialismului de bază, o estetică de recuperare a corpului și a fluidelor sale. Scopul acesteia este depășirea idealismului și a pudibonderiei, orizontalizarea, acceptarea faptului că deși capetele noastre se îndreaptă către cer, legătura noastră cu pământul, cu orizontala, rămâne esențială.

Aceeași deconspirare a infatuării omului modern de a fi depășit – odată cu desprinderea de orizontală – stadiul animalic, axa biologică gură-anus, însuflețește și portretul Doings for a Living (2018). Imaginea funcționează după modelul gros-planului deconspirat de Deleuze în cărțile sale despre cinema (Cinema I, Imaginea afect) substituind reprezentării psihologice aducerea la prezență (cu ajutorul trăsăturilor portretizate) a afectelor înseși: tristețea, frica, dorința, plictiseala. În acest caz suntem confruntați cu planul apropiat al unei guri: câmp de luptă (vezi accesoriul Nike purtat de boxeri pentru protecție), orificiu asociat cu declamarea poetică, cu actul nobil al vorbirii, cu exprimarea conceptelor și gândurilor dar totodată emblema actelor biologice de a striga, vomita sau scuipa. În acest sens, lucrările lui Mirutziu ilustrează exemplar teoria lui Bataille despre dualitatea lumii, despre dubla conotație a sacralității (sacer lat.) ce simultan semnifică sfințenia și blestemul, crima.

Adelina Ivan se remarcă în contextul unei serii de acțiuni minimaliste, recente (2020), ce intră într-un dialog relevant cu comentariul despre păr și feminitate al Pushei Petrov, cu analizele dedicate corpului și finitudinii de către ceilalți artiști. În opinia curatoarei, aceste acțiuni se înscriu într-o specie a post-performance-ului: distant, înregistrat, realizat pentru ochiul camerei de filmat, un performance din care artista face parte ca o componentă abstractă.

În Hello Vera, o cercetare pe tema feminității fragile, imperfecte în fața modelelor invincibile din reclame, artista se privește în oglindă pieptănându-și părul. Gesturile sale ritmice aduc în discuție atît statutul de obiect erotic al femeii cât și fenomenul extins al mecanizării vieții cotidiene și al prefabricării identității. Abordarea nu angajează un registru afectiv, expresionist, ci mai curând unul conceptual la intersecția dintre poezie și teoremă (vezi filmele lui Pasolini și investigația poetică a spațiului a lui Georges Perec). Corpul devine la rândul său un concept, un construct virtual. Perierea părului, așezarea și ridicarea de pe pat, trasarea unor linii pe perete sunt transformate pe rând în geometrii artistice care acționează după principiul repetiției, în gesturi rituale de exorcizare a materiei, a visceralului, de anulare a tensiunilor unei lumi nesigure și alienante.

Left square, right square, prezintă încastrarea corpului artistei în două structuri paralelipipedice. Dedublarea este doar aparent simetrică, corpul reușind să evadeze din conturul geometric doar într-una dintre cele două ferestre. Scenariul amintește proiectele lui Bruce Nauman din anii 1970 în care reprezentarea corpului era drastic afectată de percepția anormală a spațiului, precum alienanta instalație Green Light Corridor ce propune traversarea unui spațiu rectiliniu, îngust și inconfortabil, luminat de un neon verde agresiv. Critica rentabilizării și a matematizării spațiului, a reducerii formelor naturale (neregulate, circulare) la linia dreaptă este continuată în Circling, un performance ritualic în care artista se așează și apoi se învârte în jurul unui pat. Imaginea este însoțită de o a doua fereastră cu comentarii textuale despre spațiu și limbajul liniilor (drepte, circulare, organice). Reprezentarea obstinată a patului reiterează poeticele comentarii despre spațiul afectiv din Specii ale spațiului de același Perec: Patul este spațiul individual prin excelență, spațiul elementar al corpului.

Arta scoate astfel din ascundere o interpretare a dureroasei izolări a individului contemporan în perimetrul dreptunghiular al patului, camerei, locuinței, orașului. Dacă noi suntem corp iar corpul nostru nu poate fi separat de lume prin gestul simplist al decupării (înăuntru separat de epidermă de un înafară), dacă dimpotrivă corpul nostru reprezintă extensia până la care ne putem deplasa, cunoaște, atinge, atunci orice act de separare/izolare constituie o amputare a corpului. În acest sens, proiectul curatoriat de Ileana Pintilie constituie un exercițiu fenomenologic ce confirmă în limbajul alternativ al imaginii faptul că a fi nu are sens decât ca a fi în lume, că omul nu poate exista fără corp, corp a cărui izolare (pandemică) este conectată strâns de mutilarea identității.

Expoziția Identitate Ultragiată, curatoriată de Ileana Pintilie, a avut loc la Galeria Anca Poterașu, București, în perioada noiembrie-decembrie 2020.

The Infection of Identity in the Age of the Body Docile / Quarantined / Without Organs

Text by Raluca Oancea (Nestor)

Arta Magazine, March 11, 2021

EN:

In this traumatic period of insecurity and unbridled mass-media affects, when the COVID 19 pandemic is causing the gradual dissolution of natural communication, the art scene is struggling to survive, to participate in the all-so-necessary process of mediation, of debating current and at the same time painful topics. In this difficult context, the exhibition Wounded Identity proved timely, both as a chance to reinvigorate an art scene anesthetized by the pandemic and as a chance to reflect on the way in which we look at, recognize, and (re)construct ourselves.

Launched by the experienced curator Ileana Pintilie, this relevant project of identity questioning in the age of post prefixes (postmodernity, postfeminism, posthumanism) has brought together various media and approaches from cultural centers like Bucharest, Cluj, and Timișoara under the umbrella of a critique directed both at the limitations of a society based on uniformization and consumption, as well as at discrimination (assaulting, wounding, infecting, attacking) based on gender, sexual orientation, or peripheral position. The pandemic added a new layer to the problems anticipated by the curator and artists – such as their lack of freedom and power as actors in a scene dominated by institutional power centers and financial schemes, the intrusion of technology in the sphere of identity and authenticity (of the self, of art) – a layer marked by the replacement of touch and physical communication with interaction at a distance and the assimilation of masks into the pattern of the human face.

As a result, the probing of identity was related both to the theme of the body (be it the docile body, after Foucault’s model, Deleuze’s body without organs, or the sick/quarantined/hermetically sealed inside a zipper bag, as with the current pandemic) and with the types of media involved in the process of analyzing and laying bare identity through art. From her position as a reputed critic and art historian, Ileana Pintilie raised relevant questions like: what do the notions of portrait, self-portrait, and action presuppose today? How does the relation between identity and authenticity evolve in the age of mechanical/technological reproduction? Her investigation also questioned how art can still function cathartically for underprivileged genders, subcultures, and communities, in a post-performance age, in which the artist often forgoes their actual presence, retreating into a representation.

Among the exhibition’s five intermedia approaches, it is Pusha Petrov’s that most explicitly tackles the issue of subcultures. In my opinion, her works in the Bucharest exhibition continue and deepen her artistic research, marked by eroticism, pop culture, and camp sensibility (see her series of pink handbags, slightly opened, seen from above, reminiscent of an open flower or the female sex organ, Marsupium à main, Art Encounters, 2017), adding anthropological, ethnological, ontological (finitude, time) layers.

Her works exhibited in Bucharest are part of a broader artistic research carried out in Paris in African hair salons around the Gare de l’Est with the aim of exploring the ways in which hair can be a medium of artistic expression. The series of large-scale photographic portraits of African braids, titled (des)coase / (un)stitch, 2019, reveal hair as language, artistic medium, mark, taboo. The erotic connotations of women’s hair in oriental cultures are thus unconcealed: its status as an almost living, almost sacred thing that needs to be hidden, tied, bound, its capacity to simultaneously fascinate and frighten, to encompass a power relation similar to that of a religious object.

For Pusha Petrov, herself part of an ethnic minority of Bulgarians living in Banat, the project’s center of gravity resides in its participative side, in her visits to the hair salons in Paris, where they often attach extensions, and in her conversations with the members of the community. After the artist’s hair had been braided and transformed into an organic architecture by the African artists, Pusha Petrov initiated a new collaborative performance, a series of interventions with colored thread in her new hair structure undertaken by her and other artists. We see how the action of stitching hair, with thread of different colors than black, the one often used to conceal the act of production, as well as that of sewing together, everyone with their own laws, but in the context of the same communication platform, can be interpreted as subtle comments on de-construction as an artistic method and the way in which our identity is constructed in the mirror (see Lacan) and in the world (relative to a certain community, history, values).

This intermedia project, situated at the intersection of photography with performance and body art, is complemented by the sound installation Chignon Chouchou (2019), a series of buns braided in the same style that speak (with the help of internal speakers) about urban myths built around hair. The two projects are both a relevant commentary on the dissolution of specific art genres and languages, as well as an existential discourse built around the contested dichotomies between to be and to seem (here hair extensions oscillate between the status of mere appearance and that of a line of flight towards the vast territory of the transhuman), between the two interpretations of woman: woman as natural object and beautiful appearance (plant-like beauty lacking spirit) and woman as artwork, as essence and free spirit able to modify her appearance.

In the line traced by John Dewey’s pragmatist aesthetics (Art as Experience), recently taken up again by Richard Shusterman, Pusha Petrov’s research in the African salons confirms the fact that doing one’s hair is both an authentic episode of daily life and an aesthetic experience capable of bringing together a community (be it just for one afternoon in a modest room with work chairs and curtains). In this context, art practice becomes charged with existential value. It becomes a chance to debate and promote a set of (alternative) values and beliefs capable of outlining the basis for an existence and an identity based on belonging to that particular subculture.

A third work, l’image qu’on a jamais, works by the principle of surprise, the unexpected angle, or the kind of deformation seen in mannerist painting or expressionist film. What at first seems like a series of portraits without features or mysterious maps reveals itself to be representations of hairless heads seen from above, a series of alopecial configurations. The universal character of these faceless faces, capable of revealing human finitude marked by every moment that, one after another, becomes past, by Bergsonian duration, is augmented by the valuable technique of digigraphy and by the golden frames.

A precious commentary on finitude is also offered by artist Olivia Mihălțianu in her project Self Portrait as a Drowned Artist and The Portrait Studio (2020). The title reveals a reinterpretation of the famous La noyade (1840), the self-portrait manifesto of Hippolyte Bayard, who lost the status of inventor of photography to the famous scientist Daguerre, supported by the French Academy. In an original attempt to bring together the problem of identity and finitude, of the artist’s condition and how technology influences art practice, Olivia Mihălțianu picks up the message of Bayard, who, thanks to his paradoxical self-portrait as a drowned man, succeeds in defying the vagaries of fate and the limitations of technology (shooting a portrait back then required the subject’s immobility and the closing of the eyes), stubbornly remaining in art history, even if as the founder of staged photography.

Combining an exciting synthesis of media (photography, video, sculpture) with some of her favorite topics, like the self-portrait and roleplaying (starting with the exhibition Femidon, Galeria Nouă, 2007), the fragile relation between nature and technology (see her interventions in nature at the Tranzit garden or her contributions to exhibitions at DPlatform, 2018), Olivia Mihălțianu delivers a mature commentary that relates the portrait to technology, positions photo-video practice on the fine line between aesthetics and technology. In other words, the image produced with a camera, often dismissed as mere mimesis, a recording of reality, reveals in this context its capacities as a magic, spiritual tool (Robert Bresson) that can capture the beautiful, the aura, identity. The beauty of the technique, of the camera and its working methodology, based on chemicals, errors, and achievements, complements natural beauty.

The installation Self Portrait as a Drowned Artist and The Portrait Studio, in my opinion the strongest presence in the show, is remarkable in that it outlines a space within space, delimiting an independent slice of space-time. In other words, the artist constructs, in one of the gallery’s rooms, a replica of her studio in Sofia, in which, together with sculptor Stoyan Dechev, she devoted herself to the intermedial recording of the human body and identity, relative to perspective and lighting. Her subtle understanding of space defines Mihălţianu, who studied photography and video, as a transmedia artist, simultaneously illustrating the difference between mere photographer (in Vilem Flusser’s terms, the mere functionary of their apparatus) and the artist working with photography (film), probing the limits of the technical image and its interference with traditional practice (portrait, landscape).

The space is organized into four cells, of which the first two seem to be dedicated to the beautiful image favoring contemplation, bringing once more into discussion Mihălțianu’s previous studies on nature, but also her sensitive cyanotypes, some of which were made in performative-participative contexts (the old cyanotype technique was practiced by Bayard himself). In the first cell, in order to evoke the fragile status of the contemporary artist, but also photography’s relation to the limitation of the body, Olivia Mihălțianu juxtaposes a sensitive and precious salt-based print, which restages the posture of the drowned man deep in healing sleep, with a series of metal rods reminiscent of the structures used in the early days of photography to immobilize the subject. The beautiful orange photograph awakens multiple connotations, from the image of Ophelia floating on the water, calm, unmoving, and the sepia blitheness of post-mortem photographs, to the redefinition of contemplation (as the assumed solution of temporarily taking refuge in dreams, in soothing beauty) and the revelation of the principle of old photography, in which the price of the immortality afforded by representation was paid through a long exercise of bodily immobility before the camera. The second cell is dominated by a video in which images from the artist’s studio in Sofia meet images from the garden of the campus housing it, including an abandoned female bust on which rain and vegetation have left their mark.

If the first cells impressed the viewer through Apollonian beauty and invited to contemplation, the final cells are defined as a Dionysian territory of action: the shattering of the dream, the recontextualization of Bayard’s protest on an art scene dominated by institutions and market value. And so, the third room, empty and flooded with a red light that gives the space an affective dimension, combines the features of a photo lab, in which development may impose a temporary suspension of our dominant sense of sight, with the tension of the erotic, transgressive act, with a bringing to life (as painful as it might be). The final room represents a photo studio recontextualized in the selfie age, in which more and more people choose to create their portraits themselves. Here the audience is invited to use the necessary props (a support and lighting that many have already set up at home for online interactions during the pandemic) to take selfies with their own phones.

Immersive and interactive, the project offers a captivating commentary on the evolution of the technical image, from the first attempts to fix a representation in a photograph to the products of the digital age, the famous selfies, staged and prefabricated, created to be manipulated and distributed en masse. At the same time, art practice is defined as a painful and transgressive act, placed at the intersection of unlimited inspiration and imagination with finitude and humanity’s tragic condition.

One step further down the path of transgression is Adriana Jebeleanu, an artist who in 2012 chose to exit the art scene – and life, too. The story of this wounded and nullified identity is presented by exploring the register of the tragic, the strange, the unformed, and the sublime in a series of works with affective notes based on the contrast between noncolors (white, black) and a strong red. The transmedial character of these actions, which are, photographed, filmed, or performed in front of an audience, combines with an anti-art orientation, revealing an acute crisis of representation felt by the artist, who had a background in painting. One example in this sense, Blind, Deaf, Mute (2011), in which the artist sits in front of a piano without touching its keys, a (white, red, black) hood over her head, is a reinterpretation of John Cage’s famous 4’33’’.

The impossibility of communication makes Jebeleanu waver between the romantic solution of retreating from the world, of projecting disconnected dream realities, and becoming involved in cathartic actions that represent both a means of protest and an attempt to escape the self towards the other. Towards this purpose, the dream state, the trace, and absence alternate with presence – the more silent and abstract, the more disquieting.

The register of retreat is illustrated both by the performance Blind, Deaf, Mute and by short videos like I will forget, 2009, built around the dichotomies of appearance-presence, clothing-body, body-spirit. If in the first case the solution seems to be probing one’s deep interiority (one’s fears, desires, drives) in search of the last traces of authenticity, in the second case a series of white garments hung in the forest reveal the lack of a body, the artist returning to a still-free nature, to the model of spontaneous creation. The action’s register is implied when the artist decides to look the viewer in the eye, directly in the context of a performance or mediated through a video like FAST FOOD, 2008, a protest against the lack of authenticity and the machinic rhythm of life, in which the artist, dressed in white, eats the petals of a lily. Even in the video version, her piercing gaze goes beyond the optic level and into the haptic, the gaze that touches, that unsettles the audience, driving them to action.

Videos like Totally Love (2011), in which a blood-like liquid overflows from a cup, invoke the link between authenticity and angst, the act of self-abandonment, the act of flowing out of the body, the painful outlines severing us from the other now melting, an act that becomes possible (as Georges Bataille warns) only in eroticism or death. Overcoming the world of conformism, of identity void, the mechanization of life, the conventionalization of art determines the artist’s engagement in a transgressive project of probing the limits of human psychology, of the frontiers of knowledge, bringing back into discussion Susan Sontag’s definition of the modern artist as a broker in madness. In this sense, we must accept that art practice that has a cathartic aim, the performative act taken to its end, overstepping physical, corporeal limits, recovers the site of the sacred, but also proves risky for the artist as a person. In Adriana Jebeleanu’s case, the price paid for ultimate authenticity, for the experience of self-abandonment, for the acute experience of the limit, which, in Bataille’s opinion, seeks “the approval of life unto death,” was passing away.

Cluj-based artist Alex Mirutziu showcases a similar process, on the same trajectory of finitude and transgression. In his two works exhibited in Bucharest, he tests the limits of the body, gender identity, and sexual orientation. In Feeding the horses of all heroes, 2010, a performance recorded at the Accademia di Romania in Rome, a conservative, institution, the artist engages in a cathartic exercise of fall and recovery. Crossdressing as a model, a predefined object of admiration, and armed with the proper attire (high heels, provocative clothing, absent, inscrutable gaze), he traverses a catwalk under the audience’s attentive gaze. Even though, for a short time, he seems to conform to the identity of a celebrity specialized in apparent living, Mirutziu breaks the rhythmic walk through an unexpected fall (with the sound of a dramatic, dissonant metallic sound), which then repeats rhythmically. This ritual of falling (the existential coordinate philosophers associate with the loss of the authentic self in favor of impersonal qualities: what people say, think, wear) seems to invoke not just the artist’s condition and the fashion industry, but the entire society of the spectacle (Guy Debord) in which we find ourselves today hooked up as devices, docile bodies, organs, anesthetized and isolated spectators, premanufactured identities.

The contrast between fall and recovery brings into discussion Mirutziu’s research on the struggle of writer Iris Murdoch with memory loss and Alzheimer’s, confirming the artist’s ability to unconceal human finitude, the limits of the body, the will, language, endurance, of recovering the beauty and heroism that are inevitably concealed in error, in human frailty. This same contrast reveals a new kind of tension, the human being’s tension between verticality and horizontality. In this sense, Mirutziu adheres, like Baitaille and Rosalind Kraus, to an aesthetics of the unformed, of basic materialism, an aesthetics of recovering the body and its fluids. Its goal is to overcome idealism and prudishness, to become horizontal, accept the fact that even though our heads point to the sky, our link to the earth, to the horizontal, remains essential.

The same revelation of modern humans’ infatuation with having surpassed the animal stage, the biological mouth-anus axis – having emancipated themselves from the horizontal – also animates the portrait Doings for a Living (2018). The image functions after the model of Deleuze’s gros plan, laid bare in his books on cinema (Cinema I, the affect image), replacing psychological representation with bringing affects themselves forth into presence (with the help of portrayed features): sadness, fear, desire, boredom. In this case we are confronted with a close-up of a mouth: a battleground (see the Nike mouthguard that boxers wear for protection), an orifice associated with poetic declamation, with the noble act of speech, with expressing concepts and thoughts, and also an emblem of the biological acts of screaming, vomiting, and spitting. In this sense, Mirutziu’s works perfectly illustrate Bataille’s theory on the world’s duality, on the double connotation of the sacred (Lat. sacer) which simultaneously signifies sainthood and the accursed, the act of killing.

Adelina Ivan stands out in the context of a series of recent (2020) minimalist actions that enter into a relevant dialogue with Pusha Petrov’s commentary on hair and femininity and with the other artists’ analyses of bodies and finitude. In the curator’s opinion, these actions fit into a category of post-performance: distant, recorded, performed for the eye of the camera, a performance in which the artist is an abstract part.

In Hello Vera, an investigation into fragile femininity, imperfect when compared to the invincible models in advertisements, the artist looks at herself in the mirror combing her hair. Her rhythmic gestures bring up both women’s status as erotic object as well as the extensive mechanization of daily life and the prefabrication of identity. Her approach does not engage an affective, expressionist register, but rather a conceptual one at the intersection between poetry and theorem (see Pasolini’s films and Georges Perec’s poetic investigations into space). The body in turn becomes a concept, a virtual construct. Brushing hair, lying down and getting up from the bed, tracing lines on the wall, these actions are transformed one by one into artistic geometries that function by the principle of repetition, into ritualistic gestures of exorcising matter, the visceral, of dispelling the tensions of an insecure and alienated world.

Left square, right square shows the confinement of the artist’s body into two rectangular structures. The doubling is only apparently symmetrical, as the body manages to escape from the geometric outline in just one of the two windows. The situation is reminiscent of Bruce Nauman’s projects from the 1970s, in which the representation of the body was drastically affected by an abnormal perception of space, like the alienating installation Green Light Corridor, which asked you to cross a straight, narrow, and uncomfortable space lit by an aggressive green neon light. A critique of the capitalization and mathematization of space, of reducing its natural forms (irregular, circular) to the straight line, is continued in Circling, a ritualistic performance in which the artist sits down and then turns on a bed. The image is accompanied by a second window with commentary texts around space and the language of lines (straight, circular, organic). The obstinate representation of the bed reiterates Perec’s poetic comments on affective space in Species of Spaces: “The bed is thus the individual space par excellence, the elementary space of the body.”

This is how art unconceals an interpretation of the contemporary individual’s painful isolation within the rectangular perimeter of the bed, the room, the home, and the city. If we are bodies, and our bodies cannot be separated from the world through the simple gesture of division (the inside separated by the skin from an outside), if, on the contrary, our bodies represent the extent to which we can move, know, and touch, then any act of separation/isolation represents an amputation of the body. In this sense, the project curated by Ileana Pintilie represents a phenomenological exercise that confirms, in the alternative language of the image, that being means nothing outside of being in the world, that humans cannot exist without their bodies, whose (pandemic) isolation is tightly linked with the marring of identity.

The exhibition Wounded Identity, curated by Ileana Pintilie, took place at Anca Poterașu Gallery, Bucharest, during November–December 2020.

Translated by Rareș Grozea

Când Iris Murdoch te așteaptă în atelier

Text by Liviana Dan in

Romanian Contemporary Art 2010-20. Rethinking the Image of the World: Projects and Sketches”, Adrian Bojenoiu, Cristian Nae, (ed.) Hatje Cantz, 2020, p. 190-193, 204-205

RO:

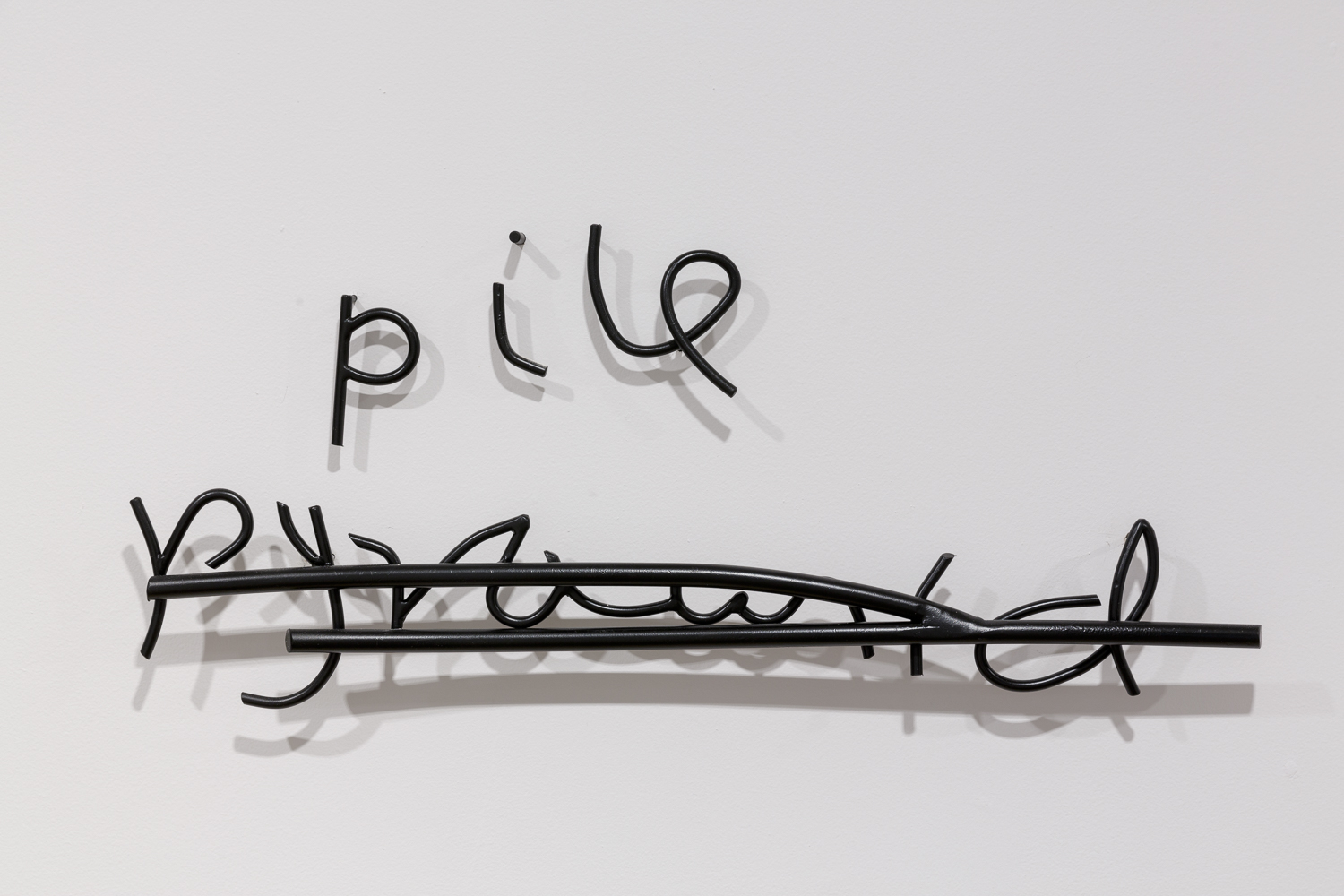

Alex Mirutziu este un poet vizual. Metoda lui de lucru este neconvențională – o meditație privată care explică limpede parcursul, teritoriul și limbajul. Defapt cele trei elemente care transformă arta și percepția. Alex Mirutziu lucrează cu un melange de practici: vorbit, scris, corp, acțiune, desen, muzică, video, fotografie.

Performanța și scrisul, relația dintre gest și cuvinte este pentru Alex Mirutziu o cercetare pragmatică pentru spațiu și loc, lucrând cu timpul într-o manieră neașteptată. În relația dintre sine și celălalt performativitatea devine o urgență.

Alex Mirutziu are o abordare tot pragmatică, apropiată de scrisul lui Wiegenstein și de existențialismul patronat de Iris Murdoch. Provoacă mereu o discuție integrală despre cum se face performanță cu obiecte, cuvinte...

Preocupat de ideologia contemporană și de formele pe care ideologia le poate lua, Alex Mirutziu este atent la material și loc. Materialul aparține printr-o tradiție narativă experienței emoționale. În organizarea materialului și locului Alex Mirutziu este ajutat de idee și de atitudine. Corpul folosește narativismul până la limita maximă. Teribil, audiența este adusă de multe ori în apropierea unor părți ale corpului. Limbajul oferă posibilități de analiză pentru corp, mișcare, imagine. Adeseori totul se desfășoară în același timp. Sursele materialului sunt eclectice. Se fac referiri la tehnicile baletului, la gesturi excentrice, la o mișcare atletică. Ficțiunea și autenticitatea nu sunt contradictorii.